本文由北京周掌柜咨询CEO周掌柜与英国剑桥大学嘉治商学院院长Christoph Loch联合创作,历时一年,以手机行业为大背景共同提炼了“边缘战略”模型。全文曾发表于腾讯深网,这里是学术精简版。同时,感谢周掌柜咨询全球化合伙人宋欣对于本文的重要贡献。即使从全球视角看,中国的智能手机行业也是一个英雄辈出、活力无限的领域。在这个行业里,大家见过恐龙的灭绝,见过武士赢得了闪亮的盔甲之后又再次丢失。今天还被奉为真理的事情,明天就可能变成了失败的导火线。在这样一场智慧和创造力相互角逐的极限战争中,有人在保卫中心地位,有人在创造新的边缘机会,但所有玩家的目标只有一个,就是成为新一代霸主。

常识是:我们每个人都知道——想要成功就必须高度聚焦。如果你同时分散精力去做很多事情,那么你不会每一件事情都做得很好。对公司来说,亦然,想要成功就必须战略聚焦。公司可以有自己的“中心”战略,公司也可以掌握和主导它们自己的核心市场、核心技术。与此同时,这些公司也有一些周边领域,也就是有长期潜力的边缘领域探索。这些领域和它们的主营业务相关,甚至可以为它们带来很多未来的机会,只不过由于目前公司没有大力将资源投入其中,导致其发展还是受限。

悖论在于:现实往往是“资源有限下聚焦”。如果我们过分聚焦的话,其实也有风险,这会直接导致你无法调整自身,从而无法跟得上外界变化万千的世界。在生物进化中,那些拥有某一方面超长特质的动物都因周围环境的变化而灭绝了。如果企业过分聚焦,那么就很难可以改变它们的聚焦点,无法从中心走到边缘的未来中心,时代变了就会被淘汰。不得不承认,这其实是一个前后为难的局面,因为转移聚焦点确实很难,而且有的时候大公司行动都很缓慢。但从另一角度来说,如果你很快改变聚焦点,那么可能会导致你浪费很多手中的资源,从而走向失败。没有什么成功是可以轻易达成的。也正因此,那些冉冉新生的新星和过气英雄的故事才让我们如此着迷。

回顾手机行业历史:手机作为智能消费电子的产业发展起步于2007年。那一年,苹果的iPhone横空出世,掀起了一场天翻地覆的革命——把手机从只能接听电话的仪器变成了我们可以随身携带的小型电脑。这并不是一场技术革命,毕竟这些技术此前就已经存在了。苹果是将这些既有的技术重新打包,从而改变了大家对于手机的认识。(其实苹果都算不上是自己研发出这个新技术组合,其实是从剑桥的计算机系直接拿走了名为“零食”原形)。对于此前从未涉足过通讯行业的苹果来说,这绝对是一场战略性的创新,从边缘走向中心的变革。在1990年代他们曾经尝试过开发名为牛顿的PDA私人电子助手,但并未获得成功。

手机从而变成了“通讯与娱乐”工具。这一改变引发了产业内部的巨变。最直接的结果:市场的领头羊,诺基亚,虽然可以做出最好的移动电话,并且还赢得了很多设计大奖。然而却无法跟上时代的步伐,最终面临被淘汰的命运,并于2015年退出了手机产业。亚洲市场的中国、韩国和日本在过去不断增长而且还高手云集。这些手机厂商都时刻紧盯着这可以用来通话、开视讯会议、游戏、照相、存储的灵活的智能手机,他们时刻准备着,并且也有能力,可以利用好每一个隐藏在这小小手机背后的机会。

而在诺基亚走下神坛的同一时期,我们可以确认的就是在2011年到2013年之间,中国智能手机行业经过长时间孕育,在3G和4G的切换时间窗口里,市场重新洗牌的机会由此而生。而之前的诺基亚、TCL、波导、HTC、三星甚至苹果等长期站在行业中心的巨头,就是被这一系列的“边缘”人和事儿打下了神坛。

本文中国手机历史崛起研究的学术版,周掌柜与欧洲知名战略管理专家、剑桥大学嘉治商学院院长Loch先生共同研究和创作,通过实战洞察和学术思考的双重维度用“边缘战略”思想解构中国智能手机行业的发展变迁。这里的故事不仅独家,思想将高度创新。

历史:中心化傲慢让国际巨头衰落

这里我们讲述中国手机从最有代表性的品牌华为谈起。2011年的三亚会议应该说是华为终端乃至华为集团的历史性转折,之前的华为B2B业务几乎都是“置于死地而后生”,某运营商高层曾公开对媒体讲:“用华为的设备我们股价会跌”,诚然,作为民营企业的华为在与中兴的竞争中天然不具备民族企业的势能高地。在经历了2002年的绝境,以及2008年经济危机的全球性挑战,华为勉强生存,且清晰的认知可持续增长的重要性,稳定的现金流就是几万人的生路。而此刻,手机成为了集团边缘业务中有着“奔小康”潜力的一个选择。

一位在华为工作20多年的老华为私下吐槽说:“之前运营商的兄弟也看不起华为手机,用苹果,只觉得通讯网络是华为技术制高点”。这或许也是激励新终端核心缔造者余承东及奋斗者们的一个心结,他在2012年被调任终端时,客观讲,这是一个“边缘的事业”。好处在于,他可以聚焦一个更广阔的战场,可以自由发明创造。

再谈OPPO和vivo。虽然早在2001年左右,陈明永就作为步步高的少数派有了单干MP3的行动,但直到2008年,OPPO都没有脱离长期以来公司做消费电子“打一枪换一个地方”的机会主义。有理由判断陈明永也是从旧的母体边缘,一步步走出来找食吃的“边缘领导者”。在2015年的R7旗舰以1300万台碾压华为之前,这家公司还谈不上什么霸气,甚至底气。陈明永和余承东的相同点在于彼此都处于企业绝对掌控者和弱势经理人之间,两者都是从一个相对边缘的位置开始实现自己的抱负,但显然余具有研发基因和惯性,陈具有工厂运营的惯性且高度关注最终用户体验。这两位“边缘领导者”与那时已经成为商界中心位置但渴望大成的雷军也算类似,承载雷军远大理想的金山软件一直在微软windows面前不温不火。而vivo的当家人沈炜虽然本是江西人,或许因为和段永平紧密合作时间更久的缘故,明显带有广东人的实用主义,更多的传承了段做企业的低调和简单,但他能够让vivo脱离步步高时代的惯性,不断下重注也展现了他的不同。

2013-2014年这段时间,中国在很多高速发展的地区涌现出了很多机会,从而引发了一场新老品牌错综复杂的竞争。那么把镜头拉回到2019年的市场,我们发现这些剑走偏锋的冒险家都走进了行业中心品牌的行列。华为和荣耀手机更是引领了这次新老交替,根据GFK、BCI等数据调研公司发布的2019年8月份的中国区手机市场销售数据,长期立足于研发的华为和荣耀已经首次超过40%的市场份额。而他们的成功要素可以总结概括为:华为发现了高端机配合独立芯片研发的边缘机会,荣耀应用了年轻化的边缘策略,OPPO和vivo在城市的边缘构建渠道和品牌,小米从Iot的边缘机会中创造了新的商业模式。当然,曾经处于中心地位的苹果和三星从没有实践过以上这些打法。从故事里,我们看到了边缘突破的偶然与必然,那么这里先阐明一下:“边缘战略”是什么?

我们必要承认,想要在要求高度聚焦的中心和要求高度适应性的边缘之间寻找到一个平衡点是很困难的。首先,边缘有很多可能,而这所有的可能都有可能是未来竞争的中心点。如果只是通过简单的分析就能知道哪一个边缘机会可能会在未来帮助我们赢得市场,那每一个人都能做到了!正因如此,在边缘机会上聚焦其实是有风险的。每一个成功案例的背后我们都能轻易找到100个非常大胆而凶悍的尝试者,只不过他们最终都没有成功。我们在前文已经提及了90年代的时候苹果失败的例子。除此之外,西门子、爱立信、微软(购买了诺基亚的手机业务)也都想要进军手机行业,然而都以失败而告终,这些公司在当时还都掌握着大量的资源。更不要说中国那些曾经呼风唤雨的巨头:HTC、酷派、乐视、魅族等。作为企业,随便看到个边缘机会就撒钱的话是行不通的,企业一定要学会选择。毫无选择的适应一切变化只会让适应的过程变得异常昂贵,那么边缘就变成了你的终结点。

这也就是为什么说对于大企业而言更有难度:在面前众多的选择中,哪一个潜在的机会是该选择正确的道路并且推动生意向前发展,而剩余的99个会导致失败?这其实也代表了与上述过分冒险态度相对立的另外一种错误的态度——过分保守,路径依赖。这背后有很多原因:首先,动力。如果我不去挖掘这样的一个边缘机遇,其实是没有人看到这个机会的,直到某些成功的企业最终取我们而代之。不过“这种事情发生的概率实在是很低!”换言之,大公司其实总是感觉自己是足够安全,不会受到这种被别人驱逐出市场的风险。如果我去挖掘到这样一个边缘机遇,这个成功概率只有百分之一。一旦失败了,大家只会看到我们的失败。上述其实是一个多面企业战略管理的艺术:我到底可以用多少创新并且承受多少失败?失败到什么程度会让我失去CEO的宝座?有时候这又和傲慢以及自大有关——因为我们很壮大、很有能力,我们自然比那些侏儒更好而且更聪明,谁能伤害我们?

对应中国市场边缘崛起的是中心的没落。苹果彻底走下神坛,这家以“极致产品”缔造“极致用户体验”的战略思想称霸世界并形成中国年轻人心中的巨人,现在陷于创新乏力的困境。通信和半导体巨子三星在中国基本消失在人们的视野,剩下的只有中国厂家对其屏幕的追捧。当然了,这种悲剧也可能发生在任何企业身上。今天还是金光闪闪的胜利者,明天就变成了作古的恐龙了。那些曾经在中国市场上叱咤风云的胜利者们站在市场的中心然后鄙夷的看着挑战者们。他们认为这些挑战者的所谓创新不过就是边缘上的小把戏,不会成什么大气候,更不可能会符合消费者们的需求。

知名管理学家田涛的著作《下一个倒下的会不会是华为》中有对更早的通讯巨头摩托罗拉的分析,也有一段类似叙述:“摩托罗拉从铱星的战略性投资失败,亏损近50亿美金,这是摩托罗拉走向衰落的分水岭。摩托不仅‘对客户需求反应迟钝’,而且走向自我封闭的‘象牙塔’”。而田涛总结的“无视客户、拒绝常识、技术至上”其实也是上一代通讯巨头走向衰败的根本性原因,背后同样源自“中心化傲慢”。

最后,(对于事物的)评判是很难改变的。在中心的成功会塑造、限制你对于什么是“正确且适当”的审美判断标准。我们之前已经提到过诺基亚的例子。他们的界面以及产品设计极其出众,甚至为他们赢得了很多设计大奖。但是当时的领导层看了看智能机的样机,然后决定——我们是希望可以连接人们(当时的市场宣传语),我们是想做人际沟通,而不是一些让人分心的游戏和摆设。他们错误的判断了下一代智能机的潜力,因为他们一直都沉浸在对于自己简单质朴的沟通系统设计的喜爱之中。

因而,我们不但需要从过去失败的大公司的经验中吸取教训,还要从众多边缘尝试的失败经验中汲取教训。这无时无刻不在提醒着今天处于中心的企业,要保持一颗谦逊的心,要聚焦在战略上,获得更多的洞察。

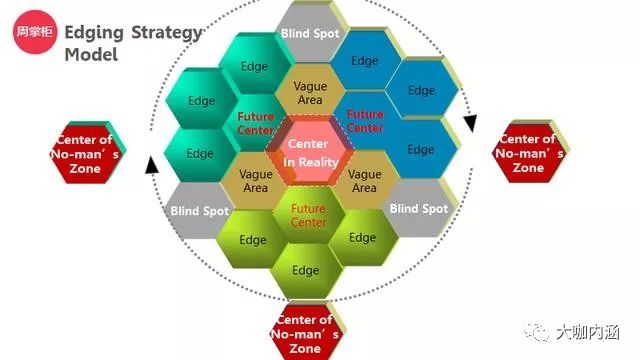

从战略逻辑上看,我们发现“华荣米OV”(华为、荣耀、OPPO、vivo、小米)在面临如此激烈的市场竞争,都在大手笔打破长期发展固定的中心化思考模式,努力思考行业未来的“边缘”所在。用”边缘战略”模型可以更清晰的解释“华荣米OV”的战略性转变,如下图:

从中我们可以感知到巨头们边缘争霸的三个大逻辑:1,打破现实的中心目的是寻找新的竞争力之源;2,优先考虑对边缘中心成为未来中心的实践;3,不排除对更远的边缘中“无人区中心”的探索。可见,这场智能手机的顶级商战中,“边缘战略”视角已经广泛应用于实战之中,去除了中心化傲慢的自我反思,每个企业其实都在重新发现自己。

需要重申的是:这确实是一个非常难以达成的平衡。因为你无法放弃当下的中心,因为你需要依赖当下的中心以赚取资源,才能投资到未来。但是你能坚持多久呢?如果现在就立刻放弃的话,那么恐怕会有现金流问题。如果一直依赖目前的中心,那么你会错失机遇之窗。想要探索边缘机遇,你所需要的可不只是深度的分析就可以了,你还需要在市场上去实践和检验这些机遇。如果同时在很多边缘机遇上撒过多的钱,颗粒无收也不是不可能。无论向左还是向右,你都有可能失败。大企业因而有变得非常小心的趋势,希望可以直接接盘那些成功的小企业。而小公司尝试得多,自然失败得也多。成功者的兴奋也总让人忘记那些失败者的悔恨。

从“边缘战略”的视角来看,竞争中危险和机遇共存的特点,他说:“如果华为可以从特朗普的打击中活下来,那么他们会不得不变得更加低调并且有弹性。因为他们现在必须开始寻找新的伙伴并且在安卓生态系统之外重新定义他们的商业模式。如果他们做到这一点,他们会变得更加强大,而美国人很可能会在很多方面输掉这场战争”。同时,华为需要提防中心化思维的“中心傲慢”,成功对于华为没有价值,真正有价值的是边缘的机会和挑战。

现实:“寻找边缘”就是“寻找未来”

不可否认,眼下最大的热点就是美国对中国手机巨头华为和中兴的打压。但美国总统给华为所带来的前所未有的危机其实也可以给华为带来很多机遇。如果把华为屏蔽在美国科技墙之外(比如芯片和安卓操作系统)确实是可以重重打击华为。但至少现在华为没有什么骄傲和傲慢的空间了,他们能做的就是动用全部的资源去重新建立联盟并且开发一个可以与之抗衡的操作以及APP开发的生态系统,这就是新的边缘化中心。而目前美国供应商也会为他们当下傲慢、过度依赖目前市场霸主地位的行为而买单。

实际上,2012-2014年“华荣米OV”的几乎都是从行业的边缘通过差异化的战略逻辑获得了高速增长;而从2015-2017年,这几家巨头都在努力夯实自己的边缘战略中心;2018年开始,随着产品差异化逐渐缩小,渠道的饱和竞争,几乎不约而同的在寻找下一个边缘。客观讲,在手机行业中国品牌前所未有的表现出超越国际巨头的战略前瞻性,背后的持续增长引擎均来自“寻找边缘”。

相对于传统巨头苹果和三星的全面优势,中国品牌的边缘是从“中国特色”开始的:首先就是差异化城市为主的中心思维,建立从农村到乡镇到中小城市,再到大城市和超大型城市的阶梯型渠道网络,配合打造贴近当地年轻人的品牌,这一点外资品牌很难下沉;而那些动则对标苹果、三星的魅族、努比亚们日渐势危。其次,从电视和广告媒体为中心的品牌传播,走向社交媒体、电视综艺合作为主的渗透式传播,这一点充满着文化壁垒;再次,从代言人为主体的明星效应到手机产品为主题的科技领导力引领,这一点发挥了中国产业链快速支撑优势;最后就是从中国主战场到全球市场的全面竞争。几乎每一步都与中心化巨头都存在高度的差异化,今天看来,确实是这些寻找到自身边缘的公司成功了。

“建能力,打中心,找边缘”已经成了中国品牌的战略共识,而“找到边缘”后,突破则需要杀手锏:华为终端产品线总裁何刚的战略思维其实也是不断寻找新边缘化技术增长点,辩证的看,Nova本身也是Mate和P系列形成中心势能后的一种边缘突破。大中华区总裁朱平区别于OV的广告和阵地战打法,提出“圈层”的垂直营销战略,就是一个层级一个层级的差异化渗透。和OV的指向年轻人品牌引领的区别是,华为更重视不同层级的政商人群对其高端机的口碑作用,所以营销中学习OV的营销渗透差异化的进行了圈层口碑渗透。而荣耀总裁赵明在坚持“轻资产、高效率”的同时,找到了被广泛忽视的极客“圈层”进行全球性的年轻化运动,通过“锐科技”谋求差异化。与此同时,OPPO的领导者陈明永借鉴华为投资100亿做技术研发并重用年轻人,vivo的沈炜不惜重金请咨询公司打造研发型全球化组织,而小米学习其他竞争对手弥补自身管控的短板。这些互相借鉴学习的案例某种程度也是一种边缘突破。尤其,华为系的崛起其实借鉴了小米和OV,但并没有复制性的对手,摸索出适合自己的打法。

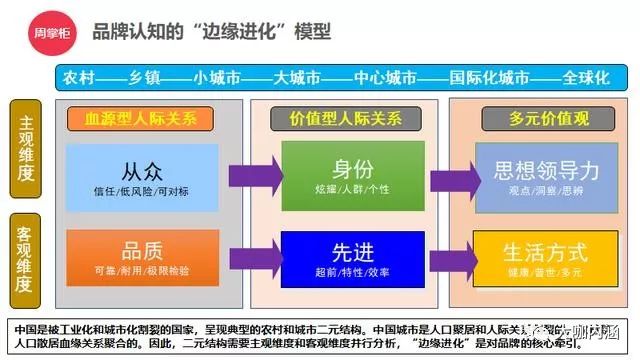

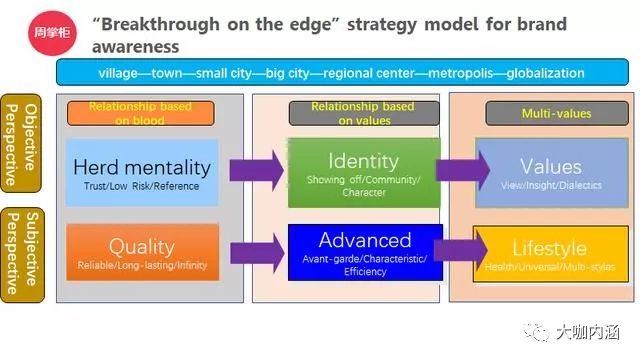

在对华为和荣耀的研究中,我们总结了品牌认知的“边缘进化“模型,同样可以反映出高水准战略竞争背后的边缘逻辑,如图:

从这个模型的大背景我们可以感知到:中国是被工业化和城市化割裂的国家,呈现典型的乡镇和城市二元结构。中国城市是人口聚居和人际关系割裂的,农村是人口散居血缘关系聚合的(在英国也存在这种二元的市场结构,发达富庶的南方和贫瘠落后的北方拥有完全不同的视角,这一点也可以从脱欧的投票结果中看出来,害怕全球化带来负面影响的北方是坚定的脱欧派,而享受全球化红利的南方则是留欧派),而全球化市场其实兼具两者的特点。因此,多元结构需要主观维度和客观维度并行分析,重视“边缘突破”方向中的品牌逻辑。

通俗一点说:看中国的二元结构,底层在消费电子需求上更接近于“从众”和“品质”两个视角,这要求消费电子厂家形成低风险、可信任、可对标、可靠、耐用及经得起极限检验的产品;而对于上层的工业化和城市化人群,更接近于“身份”和“先进”两个视角,要求厂家对炫耀、个性、超前、特效和效率要素深度关注;放到全球视角,主要的两个要点则是“思想领导力”和“生活方式”引领。

这种城市/乡村人口之间的差异并非只存在于中国。根据诸多的文化研究表明,越是在贫穷的国家,社会越是层级分化明显,人们越是遵从这种社会秩序;而在富裕的国家,往往主张平等主义,人们表现得更加具有个人主义倾向。为什么会这样呢?因为穷人更加依赖彼此帮助以走出自己面对的困境。因为他们彼此依赖,他们需要一个很好的互利互惠的关系才能维持彼此团结。因而如果一个人开始炫耀了,那么会招致其他人的反感,并且下次也不会帮助他了。而城里人的这种炫耀行为其实是跟他们富足的资源有关。因为富足,所以不那么依赖他人,从而不那么需要其他人对他“看得惯”,表现得自然更加随性。

此外,鉴于该文化研究在过去三十年内重复了两次,你可以看到有一些国家已经变得更加富有,随着人们已经不再依靠他们的家族活下去,他们变得更加以自我为中心(炫耀自己的花销能力其实是在这种情况下产生的,而不是因为家族给予的!)。而中国社会的农村vs城市二元结构正好就是展现了这一点,所以给企业的启示是:要了解你的客户人群的文化标识。即使在同一个国家,他们之间也可以有很多不同之处。我们可以得到的结论是:感知到消费者的情感收益是品牌寻找边缘的基础思维方式。

理论:东方哲学融合西方科学

实战,注定要比学术思维更加丰富,但学术层面的探索往往更有哲学的趣味。

2019年,随着中美贸易战向科技战的演化,华为成为了全世界范围内讨论最多的科技品牌。而任正非的对外展现出的思想领导力被广泛好评。与此同时,OV和小米对于生活方式品牌的快速拉升也引人注目。中国手机行业几乎成为了中国制造中融合西方科技美学最充分的行业,当然,骨子里也渗透出浓郁的东方哲学思想。

通过以上战略分析和思想对话,似乎可以有一些更加大胆的结论。从边缘化战略实践推理来看,如果用未来5年到10年的大周期看目前的手机巨头竞争:OV和小米的突破方向大概率会在海外市场,人们曾经认为的“厂妹机”不仅会永远停留在历史里,获得美国和欧洲的市场份额也将获得可能,这个边缘突破,也许他们自己也没那么确定,但在不断探索边缘的过程中愈发清晰。反而华为品牌在寻找边缘的过程中,面临最大的战略挑战可能是中国市场中心化成功、功能至上这两个战略陷阱,在寻找边缘的过程中,不排除围绕Android操作系统或者自身鸿蒙操作系统构建的全新开发者生态,围绕芯片的能力扩散形成基于基础能力的开放平台架构,全面开放授权不无可能。荣耀反而有可能突破长期与华为品牌的中心化捆绑,更差异化的探索”锐科技”边缘,比如突破为泛Iot、家电、手机的全渠道品牌。用10年甚至更长的角度看,华为系的消费电子基因更加纯粹大概率是边缘延展的必然结果。大华为本身就是从运营商网络到无线业务,到终端业务到泛Iot和云服务业务这样边缘突破而来,有理由相信,这也是任正非所言“熵减”的真实路径,边缘同样是对中心的耗散和再造。

另外,两个手机功能边缘化的临界点可能很快出现:一个是消费者兴趣目标的偏离,比如从视觉拍摄到多媒体或AI的可能性,另一个是消费电子市场饱和后的消费降级,有可能让柔性的服务替代刚性的设备增长成为新的战略边缘。对华为终端而言,由于长期对于产品高度聚焦,对于品牌、用户运营和云服务则一直处于边缘地位,华为系的最后增长点也大概率就在这里,我们应该可以看到云服务更激进的引领边缘创新。

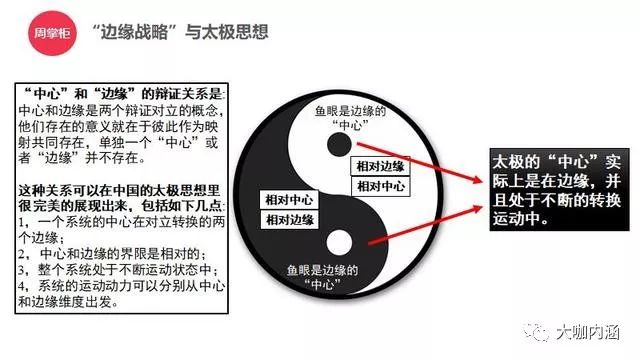

这一系列边缘战略的逻辑推演和转化,有意无意的体现了中国传统文化的太极的阴阳辩证思想,不妨做个对比。太极图中:其一,没有绝对的中心,一切都是运动中的黑白,中国手机品牌自己和友商其实互为战略映射;其二,“鱼眼”是逻辑反面的映射,他们是一种走向另一端的驱动力,也就是说:别人战略动能很可能是你未来的战略增量逻辑;其三,“阴阳”本来就是同一事物的正反两个方面,非黑即白的战略思维注定被运动和时间吞没,就是灰度,从运动的角度看手机争霸其实也是阴阳融合的过程。应用这个哲学思想,太极的本质也是在将中心和边缘在运动中的逻辑关系。所以,华为和荣耀都像是一个太极系统的黑白,OV彼此也应该如此,甚至华为系和OV小米也可以放在太极中感受到他们的动态渗透和变化的大逻辑。

中国企业阶段性成功的背后,确实充满着值得总结的深刻战略甚至哲学基础,“边缘战略”思维不仅符合东方哲学的阴阳辩证,也基于西方科学精神的解构主义。

其一,边缘战略承认一个组织应当是多维的,因而它的“战略核心”是模糊的——它可能追求高销量、也可能是希望可以做出让顾客满意的产品、再或者是组织好的声誉,边缘战略模型就是突出强调组织活动“中心”的动态模糊性。所谓的中心就是你投入最多人力、物力,当下营销最侧重的地方。这个你认为的“中心”可能是在某个维度的中心位置上,并且在驱动你的组织,但是它不是其它维度上的中心,在其它的维度上它是无力驱动组织的。随着我们的视角的变化,中心也在发生着变化。而这正好也反映了中国手机品牌的模糊性和多面性。

其二,边缘战略模型也承认变化在无时无刻的发生。今天或许还被我们当成是战略制高点,明天就变成了累赘。在我们如今全球多元动态的商业环境中,并不是一个所谓的“变不变天”的问题,而是“什么时候”的问题。因此,我们当下所经历的“中心”可能在,或者不在,再或者不再在你的价值主张定位之内。也正因如此,边缘战略模型内化了战略变化的本质。它鼓励你不要只关注眼下,而要用更长远的视角去思考,组织有何而来,又去往何处。

综上,中国手机行业历史性崛起的深刻逻辑在于行业领先的战略能力,在这场世界性的顶级公司参与的强手争霸中,中国手机品牌不仅学习对手,也不断从自身的边缘视角寻求机遇。“华荣米OV”五大品牌不仅体现了东方哲学的实用主义,也同时深刻的学习西方管理科学模块化推动战略和组织的联动变革。而今,中国手机品牌几乎成了中国制造最闪亮的名片,从更高级的战略竞合关系中,通过不断寻找新的“边缘战略”动能,变化中体现着生机。

究其根本,顶级商战中,“边缘战略”对于“华荣米OV”来讲不仅是中心化的防腐剂,更是牵引未来的核心思想。边缘视角不仅让各大厂家谦虚学习友商和奋斗自强,更能从未来看现在,勇于突破、坚定聚焦,这或许就是中国手机品牌崛起的深刻逻辑。

附:全文英文版

Edging strategy: the logic behind Chinese booming mobile industry

Yu Zhou, Christoph Loch

The Chinese mobile phone industry is a great dynamic environ-ment where we have seen exciting tales unfold. It has seen di-nosaurs slain, knights winning shining armor, and knights losing their armor again. What is right today may be ineffective tomor-row, in a battle of wits and creativity in defending the strategic center, and inventing new edges that grow.

We all know that in order to be effective you need to have focus --- if you try to do too many things, you won’t do them well, or fail. This is also true for companies, who need strategic focus. Com-panies have “core,” or “center” strategies, center markets, and center technologies, which they master and serve well. They have peripheral areas, their “edge,” which are relevant and pos-sibly represent future opportunities, but which are given only few resources --- that is what focus under resource constraints means. But there is also a danger in too much focus because it prevents you from adapting to the world that changes around you. In biological evolution, animals who are too specialized go extinct when the environment changes. Companies who are too focused, and are not capable of shifting their focus, from core to edge, get left behind. But this is a hard dilemma --- shifting focus is hard, and sometimes large companies are too slow. On the other hand, if you shift too easily, you waste too many resources and may also fail. There is no easy recipe for success. This makes for the fascinating tales of strategy, with rising heroes and fallen heroes.

The modern consumer mobile industry (i.e., the general purpose devices we know today rather than just phones) started with the Apple i-phone in 2007, which revolutionized phones from talking devices to the general small computers that they are today. This was not at heart a technology revolution --- as they had done be-fore, Apple took existing technologies from others and recom-bined them in a new package that changed people’s attitude to the device. (Indeed, even the new package had been developed in the Computer Science Department of the University of Cam-bridge in 1999, called “Snacks,” which Apple took over). For Ap-ple itself, this was a strategic innovation, a move from the edge to the center, as they had not been in telecommunications be-fore. (They had tried with a “personal digital assistant”, or PDA, called “Newton,” in the 1990s but failed.)

The shift to the new “general communications and entertain-ment” device caused havoc in the industry. The dominant mar-ket leader, Nokia, had the best mobile phones (winning design awards in the process), but was unable to make the shift to the edge and declined, and exited the industry by 2015. Now our story begins, in China. The Chinese market grew huge and fea-tured many players that were ready, and capable, to take ad-vantage of the opportunities inherent in the flexible devices that allowed talking, videoconferencing, gaming, photographing, stor-ing, etc.

After 2011, as 4G was replacing 3G, the Chinese mobile phone market saw a reconfiguration. Nokia, TCL, Bird, HTC, Samsungs and Apple, who used to stand at the core of the mobile market, were beaten by the brands and people on the edge.

History: hubris at the center that led to the fall of world gi-antsOur story starts with Huawei. A internal strategic meeting in Sanya in 2011 was a turning point for Huawei mobile and even for Huawei Group. Before, Huawei’s B2B business was strug-gling on the edge of bankruptcy. Some Chinese operators even said publicly, “Our share price will fall if we choose to use Huawei equipment.” As a private company, Huawei certainly did not enjoy any privileges compared with, for example, ZTE inside China. Huawei had gone through a very difficult period, such as an impasse in 2002 and the global challenge in 2008 due to the financial crisis, and started to understand the importance of sus-tainable growth. The only possibility for them to survive was to have stable cash flow. And among all their business units, the mobile business, which was still “on the edge of Huawei group’s strategy”, was the most likely one that might help them out.

One veteran employee from Huawei complained, “Our own staff from the B2B unit look down on us (the B2C unit) and prefer to use Apple than our own products. They think that only the tele-communication equipment is our technological commending point.” But this kind of remarks actually motivated Huawei’s B2C unit, especially its head Richard Yu, who was promoted to this position in 2012, a "marginalised guy” entering into a “business on the edge”. The only advantage he had was to focus on this wide battlefield where he was free to maneuver.

Now we come to two other key players, OPPO and vivo. Chen Mingyong was already back in 2001 one of the few visionaries who wanted to leave BBK while it was at the peak of its success in consumer electronics. He left BBK and founded OPPO in Dongguan, Canton Province. He was seen as an audacious leader who dared to leave the center in order to search for op-portunities on the edge. OPPO had little confidence until 2015, when it sold 130 million devices of its R7 flagship model and beat all of its competitors, including Huawei. Chen Yongming and Richard Yu were perhaps not brilliant professional manag-ers, but they had control of their business units. They were both on an edging position to start their new career chapter. Turning to vivo - Shen Wei, veteran employee of BBK, later also left the company to found vivo. He had worked many years with Duan Yongping, founder of BBK, he embodied typical Cantonese characteristics, being pragmatic and low-profile. But in the end he managed to get vivo off BBK’s routine and made it one of the most successful brands in China.

During 2013 and 2014, the story continues with an intricate competitive dance of old and new players fighting for the oppor-tunities in the huge growing market. If we look back at the market in 2019, we find all these audacious adventurers among the most successful brands. To a certain extent, Huawei and Honor led this market transformation. And according to GFK&BCI’s sta-tistics of the second semester of 2019, Huawei and Honor to-gether take up a market share of more than 40%. Their success of these players can be summarized as follows: Huawei devel-oped the edge opportunity of combining a high-end device with independent chip R&D; Honor focused more on young people; OPPO and vivo built their solid distribution channels outside the urban areas; MI saw a new business model in IoT. In compari-son, Apple and Samsung, who stayed safely in the center, nev-er tried any of these. These stories illustrate the need for an edging strategy in dynamic markets.

But after these examples, maybe we need to explain what edg-ing strategy exactly means. Let’s emphasize right away that this is hard. It is difficult to achieve a balance between focus (effi-ciency of the center) and adaptation (edge flexibility). First, the edge has many candidates for where future competition might go. If we could through analysis find an answer which edge op-portunity will win in the future, everyone would be doing it! Therefore, investing in edge opportunities is risky. For every successful example we described, we can easily find 100 ex-amples of aggressive and audacious (cocky?) wannabes whose ideas failed. We already mentioned Apple’s first failure in the 1990s. Just some examples --- Siemens, Ericsson, Microsoft (by buying Nokia’s remnant mobile business) all tried to enter mobile phones and failed, and they all had plenty of resources. Not to mention the myriad startups and small companies that tried in China, such as HTC, Coolpad, LETV and MEIZU. You can’t throw money at everything that might become an opportunity in the future, you have to choose. If you are too adaptive, the ad-aptation will become too expensive, and then edging can be-come fatal.

That’s why this is not so easy for a large company: which poten-tial opportunity is the right one that can evolve our business, versus the 100 failures, and shall we invest at all? This repre-sents the other direction of error, being too conservative rather than too adventurous. There are many reasons for this: first, in-centives. If I do not develop an edge opportunity, no one will see the missed opportunity (until, of course, one of the few success-ful ones indeed takes our business away, but let’s face it, “this happens rarely!”, in other words, large companies feel protected enough to underestimate the risk of having their business taken from them), but if I do develop one edge business, and it’s one of the 100, it will fail, and everyone sees our failure. This is part of the art of strategic management in a multi-divisional firm: how many bets and failures can I carry in order to be agile enough? When do the failures become so many that it will cost the CEO’s job?

This connects to arrogance and hubris --- we are big and power-ful, we are better and smarter than the dwarfs, and who can hurt us? Look at Apple, who have fallen behind in China because of their lack of innovation. Yes! Although people all over the world still talk about Apple as an innovative company. Telecom and semiconductor giant Samsung faded away from the sight of Chinese consumers. What is left is only their screens which stay still very popular in China.

Of course, this can catch up with anyone, and the shining win-ners of today may become the arrogant dinosaurs of tomorrow. The former successful companies in China were standing at the center and looked hubristically down at the new challengers. They all believed that the innovation of these challengers would always be on the edge and stay far away from the consumers’ needs.

Mr. Tian in his book also took Motorola as an example. Due to the failure of the SpaceX investment, Motorola lost nearly $5 bil-lion and started to fall. Motorola was very slow vis-a-vis con-sumers’ demands and locked themselves up inside their own ivory tower. All this resulted from its central hubris.

Finally, judgment is hard to change. Being successful in the core shapes, and constrains, your aesthetic judgment of what looks “right and appropriate.” We have already mentioned that Nokia won design awards for their beautiful and functional user inter-faces up to 2007. When the Apple smartphone came along in 2006, Nokia even had fully comparable technologies. But the managers looked at these prototypes and decided, “We are about connecting people (that was their marketing slogan), about communication, not about silly detracting games and oth-er knick-knacks.” They misjudged the potential of the new gen-eralist device because they loved the frugality of their communi-cation designs too much.

Therefore, what we learn from the failure of the former giants, but also from the failure of many edging attempts, can be very alarming for the companies at the center today who need to be humble, focused on strategy and gain more insights.

From the perspective of strategy, Huawei, Honor, MI, OPPO and vivo have all invested to break their routinised center strategy and have tried to figure out which edge has potential to be the future center. This is explained by our edging strategy model (in the following figure):

We can see three logics of competition on the edge: 1. find pos-sible new battleground for future competition, with the explicit in-tention to break the current center; 2. find out which edge has the potential to become the new center in the future; 3. extend the edge towards “no-man’s-land” to explore more opportunities. The edging strategy perspective has been used widely by all the players involved in this smartphone business competition. Each of them has rediscovered itself by leaving the center and going to the edge.

We repeat that this is a difficult balance to strike. You can’t just give up the current center because it earns the resources today to be invested for the future. But how long is too long in holding on to it? Give it up too fast, and you lose your cash flow. Hang on too long, and you miss the window. Exploring edge opportu-nities can’t just be done with smart analysis, you have to devel-op and test them in real markets. Throw too much money at too many edge opportunities, and you may also lose. You can lose by erring in either direction. Large companies have the tendency of being too cautious (for the reasons explained earlier), relying on the ability to buy winners. Small companies experiment more, and realistically also fail more. Our stories of the winners need to acknowledge the many losers.

If a company can avoid hubris, a challenge from the edge can actually carry opportunity. Ironically, the existential challenge imposed for political reasons by the US President on Huawei may also carry opportunity. Yes, locking Huawei out of US tech-nology (such as chips and the Android operating system) is an existential threat. But now there is no room for hubris, but only for mobilizing all resources to develop new allies and develop a rival ecosystem of operating system and app developers. In a situation like this, many have concluded that we may need an alternative to US tech dominance. If Huawei can pull this off, it may come out stronger than before, and hubristic over-reliance on a current market dominance may come back to haunt US providers.

Practice: “searching for edge” is “searching for future ”During the period 2012 to 2014, the five companies Huawei, Honor, MI, OPPO, and vivo, emerged from the edge of the mo-bile sector and gained market share because each of them adopted some strategy of differentiation. During the period 2015 to 2017, the five companies consolidated the foundation of their edging strategy’s center; and from 2018 on, as the difference between them was fading away and the market started to be-come saturated, each of them has started to search for the next edge. Chinese mobile brands tend to have more forward-looking strategic plans than their international competitors. And their long-lasting growth is the result of their willingness to search for edge.

Compared to the other two global giants Apple and Samsung, who had a privileged position, the Chinese brands’ edge strate-gy relied, first, on intimate knowledge of Chinese market charac-teristics: they abandoned their city-oriented center strategy and built an echelon web of distribution channels covering at first ru-ral areas (small villages and towns), then small and medium sized cities, and then large and super-large cities. It is more diffi-cult for foreign competitors to build up such complicated distribu-tion channels. Second, the five replaced TV and other traditional branding platforms with social media and TV shows, where they could place advertisements in an indirect way. Third, they re-placed celebrity-focused endorsements with technological lead-ership, which also demonstrated the advantages of Chinese supply chains. Last but not least, they widened the competition from the national level in China to a worldwide level. Chinese brands differentiated themselves from their international compet-itors during each step. And searching for the edge offered them the differentiation. “Capacity development, center breakthrough, edge identification” has already become a strategic consensus among Chinese mobile companies.

Huawei’s mobile strategy can be summarised as follows: After years of preparation, the Mate and P series became popular and therefore the center. The new Nova series was a way to identify a new edge. Huawei was good at “positional warfare” (meaning developing long-term trust relationship with retailers), and “circle and tier vertical marketing” (meaning penetrating so-ciety circle by circle and tier by tier), where promotion was ad-justed to each circle’s and each tier’s characteristics. In contrast to OPPO and vivo, who focused more on promotion via adver-tisement and concentrated on young people’s needs and tastes, Huawei concentrated more on its high-end models’ reputation among businessmen, civil servants and politicians. Huawei and Honor learned from OPPO and vivo to adapt their marketing strategies to meet the needs of each consumer category sepa-rately. While the “elder brother” Huawei focused on the middle-upper class, the “younger brother” Honor targeted other catego-ries of consumers, such as fans of extreme sports, which be-came popular among youngsters worldwide.

In the meantime, Chen Mingyong, CEO of OPPO, invested RMB 10B in R&D and put rather young people in highly important po-sitions; Shen Wei, CEO of vivo, hired globally known consulting firms to develop his organisation into a global one; MI tried to catch up by improving its management and control. Therefore, their achievements were based on one anothers' successful experience. They never directly copied one another but rather adapted to reinforce their own strategy.

We summarize our study of Huawei and Honor in the following “edge evolution” model, which reflects the logic behind their strategy:

This model reflects that China has a different society structure than Western countries: China is characterized by a dualistic structure. Following the twin processes of industrialization and urbanization, China has two totally different faces. The urban part of China has a very dense population with fragmented rela-tionships between people (it is more “westernized”), while the ru-ral parts of China have a sparse population with closer relation-ship among people (we can, actually find such duality in other markets as well, even in the UK, where the tension between the urban South and the rural North contributed to the Brexit vote). We can also identify such differences in a globalized market. Therefore, to analyze such a multi-cultural structure, we need to understand not only the “objective” sociology but also each cus-tomer’s subjective perspective.

Reflecting the differences in sophistication in the Chinese dual-istic structure, we find some that people with a disadvantaged background exhibit more “herd behaviours” and prefer to buy electronics of “good quality”, meaning reliable, low-risk, credible and durable. In contrast, people from the upper-middle class in the industrialized and urbanized cities prefer to have phones that reflect their social status and demonstrate superiority over other devices. The mobile companies need to feed this desire with avant-garde, high-tech, sophisticated (etc.) characteristics. Dif-ferences in values (self-identification) and life style drive product features.

This difference between rural and urban populations is not spe-cific to China: we find in national cultural studies that poorer countries tend to be more hierarchical and conformist, while richer societies tend to be more egalitarian and more individual-istic rather than group oriented. Why is this so? Because poor people are dependent on help from one another to get by, and need to foster good reciprocal relationships of mutual solidarity, and if one shows off, the others resent you and may not support you the next time. Urban consumers’ showing off behaviour is related to their higher affluence, which makes them less de-pendent, less willing to suffer for support from others, and more self-indulgent.

Besides, as studies were repeated twice over 30 years, we could see how societies that became richer moved toward more egalitarianism and more individualism as people were no longer dependent on their clan to survive. Showing off then expresses power, which emerges rather than being given by the clan! This explains the difference between the rural and the urban com-munities in China: within the same country, urban populations have become rich and moved toward individualism and status behavior, escaping the rigid hierarchies and solidarity webs of the poor. The lesson is that you need to understand the cultural symbols of your target customer population. Even within a coun-try, they can differ a lot. It demonstrates how important it is to understand the emotional benefits of one’s products to achieve a breakthrough with an edging strategy.

Theory: a mixture of eastern philosophy and western sci-ence of managementPractice brings certainly more experience, while theory enriches our understanding (and generalizability) of the experience.

In 2019, as the trade war between China and US continues, Huawei has suddenly become the most known tech brand. At the same time, OPPO, vivo and MI gain more and more popu-larity from their strategy of brand upgrading. The Chinese mobile industry seems to succeed in distancing itself from the “medio-cre” Made in China reputation, and is becoming a successful example of combining Eastern philosophy with the Western sci-ence of technology.

Based on our analysis of the Chinese mobile industry’s edging strategy over the last 10 years, we dare to speculate about the next 5 years: First, OPPO, vivo and MI are likely to achieve breakthroughs in foreign markets. The “factory girl’s phone” will gain popularity and market share in the US and Europe. This edge seems to be increasingly clear for them while searching for their future potential.

Second, Huawei may, by the political context, be forced to de-velop a new open ecosystem be it based on Android or their own Ark OS, with open authorization (although they have stated that they will not abandon their partners unless they are forced to). Honor, as part of the Huawei group, might finally get a win-dow of opportunity to be detached from Huawei and search for its own edge, such as developing itself as a rich brand covering IoT, electronics and mobiles. Huawei has a tradition of achieving breakthroughs on its edge: from operators/network service to wireless network service, from B2B to B2C, from mobile busi-ness to IoT and Cloud. Therefore, Huawei may well continue to find more opportunities on the edge and broaden its hardware as well as software range (especially with AI and machine learn-ing). This corresponds to Ren Zhengfei’s entropy theory -- going to the edge as a way to rebuild the center.

This will likely happen in the context of two big changes within the mobile industry: one is the change of consumers’ focus, such as from visual photo shooting to multimedia or AI shooting; the other is a consumption shrinkage after the market becomes saturated. Service is likely to replace the device as the driver of future growth. This will require Huawei to widen its capabilities, as it has always focused on the hardware product at the cost of branding, consumer relations management and Cloud service. These are still on the edge of Huawei’s strategy. But that is also where Huawei can find their next center. Cloud Service and Ai will be leading the edge innovation.

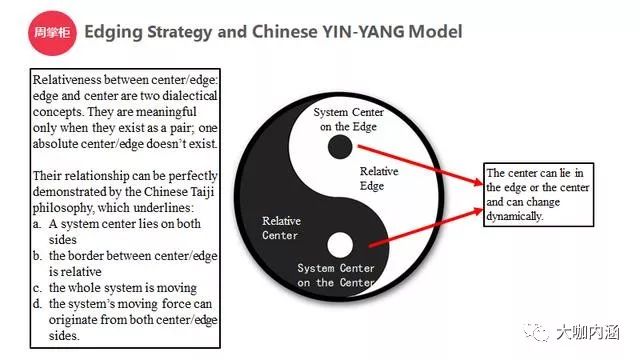

All these theories are consistent with the traditional Chinese dia-lectic philosophy of Yin-Yang (see the figure below). Yin-Yang suggests first that the center exists not as an absolute, only as the opposite to the edge. Second, either of the two centers may give you an impetus to move forward. Third, Yin-Yang means itself the two sides of one thing but it also points out the ambigui-ty of the boundary in-between. Yin-Yang can be also seen as the forever-lasting change between the center and the edge.

Thus, the success of Chinese companies at this stage can be interpreted in the spirit of Eastern Yin-Yang dialectics, but we can also interpret it with the Western science of management: The Edge Model acknowledges that the goals of the organiza-tion may be multidimensional, and therefore the “strategic core” is ambiguous --- is it the profit machine, or the piece that makes customers the most loyal, or the piece that supports most strongly the reputation of the organization? The Edge model emphasizes the ambiguity of the “center” of your activities, meaning the area where most of your people and resources are focused, and where the market positioning currently lies: it is possibly at the heart of one dimension of the goals that drive your organization, but maybe it is off the center, and less power-ful, on other goal dimensions. What the center is changes de-pending on the viewpoints of stakeholders. And this reflects the ambiguity and multifaceted nature of today’s world.

Secondly, the Edge model acknowledges change. What is the center of our strategic position today may become a liability to-morrow --- this is, in today’s dynamic global business environ-ment, not a question of “whether”, but a question of “when”. Therefore, the center of our current activities may lie in an area that is not yet, or not any more, in the center of our value propo-sition positioning, or in the center of what stakeholders expect. Thus, the Edge Model embodies the changing nature of strate-gy. It encourages us to think about where we came from and where we are going.

In conclusion, we assert that the Chinese mobile industry’s dec-ade-long rise results from the Chinese companies’ strategies. While competing with global giants, the Chinese companies knew how to learn from the others and how to find more oppor-tunities on the edge. The strategies of the five top brands Huawei, Honor, MI, OPPO and vivo, embody the Eastern phi-losophy of pragmatism but also the Western science of man-agement, which guided them to advance strategic and organisa-tional reform. Today, the Chinese mobiles brands have become the shiniest name card for “Made in China”. While searching for new edge, these companies motivate themselves to continue to go beyond the boundary.

The edging strategy is not only a way to prevent the center from becoming stale, but it also acts as a force to drive them forward. Edging strategy allows them to remain humble and learn from one another. It encourages them to strive for breakthroughs in focusing on potential edge. And this might contribute strongly to their success.

作者介绍:下图为2018年中旬摄于英国剑桥大学校区酒店,在当天的交流中Christoph Loch院长对于结合中国传统文化思想的战略研究合作非常感兴趣,大家共同做了深入探讨,并在1年后有了这篇深度文章。

周掌柜,北京周掌柜管理咨询有限公司CEO,多家全球化公司战略顾问,专栏作家,曾就职于美国美世咨询等咨询公司。

Christoph Loch:英国剑桥大学嘉治商学院院长,德国人,曾就职于麦肯锡等咨询公司。